Essay: Defining Success

Success can only be measured by comparing results to original goals. Within our project we had two major components: the Vendée Globe 2016; and our sitesALIVE! education program based on our participation in that race.

Our objectives for the race were to finish, and to finish in less time than 2008-9, which was 121 days. We have not yet finished, so we cannot say yet that we succeeded. We are still at sea and racing, whereas 11 have had to drop out for various reasons. The boat is in pretty good shape and the skipper too, although both are tired.

With our school program, there were two sides to our goals. The first was the technical production of the program and its expansiveness. We wanted to make it truly international, have it be in multiple languages, to deliver our content on a rigorous schedule so that teachers could absolutely count on it being there when we said it would be, to support multiple distribution methods (newspapers, web, social media), to contract with various distribution partners globally for further widening of our network, and to assemble a Team of Experts without peer. We have done all of these, so the technical production can be declared a success.

Yet the ultimate goal was to engage and excite students in learning with our unique approach to using the real world to showcase and explain different subject areas. Whether we have succeeded in this will be a question for you, the students and teachers using the program. We have had good encouragement from many of you so far, but we will have to finish our program completely, and then look back at what we hear from you. We keep our fingers crossed that it has worked for you – that will be the ultimate test for whether we have succeeded or not.

We thank you immensely for your participation.

Essay: Defining Success

Has Rich been successful in achieving his goals? At the start of the race Rich said he wanted to sail well and write well, to share his story with those on land, to deliver the sitesALIVE! content and to finish the Vendée Globe. He wasn’t defining success by winning or losing the race, since that was not his primary goal. Success can be defined in many ways.

Rich entered the Vendée Globe race in part for the challenge of the race, but mainly for the opportunity to create the sitesALIVE! education program designed to excite and engage students and families around the world. He says, ‘Once you’ve hooked kids with excitement, you can feed them whatever content you want—math, geography, teamwork, goal setting and more.”

Was his sitesALIVE! education program successful? Absolutely! Rich called in audio podcasts via his satellite phone, wrote Ship’s Logs, answered students questions, wrote essays in great detail, created videos of the gales, crossing the international dateline and prime meridian and on The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, among others. With help from his shore team, he also published a weekly print series that has appeared in newspapers around the world, Rich did this while sailing the Great American IV in difficult weather conditions, on dangerously high seas, in the heat and freezing cold, over the course of more than 25,000 nautical miles.

Rich has been followed by thousands of students in classrooms and families around the world. He has received very positive feedback and support from his followers. These point to the success of the sitesALIVE! education program.

Now we anxiously await Rich to cross the finish line in Les Sables d’Olonne and complete the Vendée Globe. Thank you Rich Wilson for your inspiration and perseverance in successfully completing the Vendée Globe with the admirable educational goals that you set up for yourself. We admire you!

Essay: What I'll Miss

At the end of this big effort to sail around the world singlehanded, it will be time to reflect on what I’ll miss from these offshore days when I am back on land.

I’ll miss the very clean air of the ocean and how my lungs love it. I’ll miss seeing the flying fish whiz here and there trying to escape from our boat that they perceive to be a predator. They fly for 150 yards on their fins – it is amazing! I’ll miss the amazing albatross of the south, who glide on their long wings for days, weeks, months, hardly ever flapping their wings, they are the perfect aerodynamic machine. I’ll miss the stars of the Southern Hemisphere that we can’t see from the north where I live, because they are different, and they are an adventure.

From this race, I’ll especially miss the almost daily communications with fellow competitors. We are all challenged by the sea, we are all doing our best, we are all having highs and lows in our minds and spirits, as well as in our weather systems. My friends of the south especially have helped to sustain me, and, I’d like to think, perhaps I helped to encourage them a little bit too.

I’ll also miss the interactions with our sitesALIVE students around the world. I’ve had the marvelous chance to bring a bit of the ocean to you, 70% of the planet, but unseen and not experienced by so many. These interactions I will miss the most.

Essay: What I'll Miss

The end of any great adventure brings a variety of feelings. First there is a sense of relief that comes from an end to the dangers and deprivations that have been endured. Then comes a sense of accomplishment from having worked so hard and long to achieve a very difficult goal. Rich will soon have circumnavigated the Earth solo nonstop not just once, but twice, an incredible accomplishment!

After being on the ocean, or any wild remote place for a long period of time it can be challenging to readjust to the “normal” world. Things we often take for granted like running water, fresh fruit, television, and a soft bed are much appreciated luxuries. On an expedition your priorities are different, and senses sharpened. You have to constantly innovate, solve problems and adapt. It is always nice to get back to civilization and all the comforts of home, at least for a while.

Then, despite all the hardship and fear, you start to reminisce about the amazing places you have been, and things you’ve seen that few people will ever experience. The shared experience of a challenging expedition often brings participants closer together and the friendships forged can be quite deep. While the comforts of home are appealing, to some people a life well lived means a series of great adventures. So, don’t be surprised if you see Rich Wilson set sail on yet another epic voyage, continuing to inspire people around the world to pursue their own dreams.

Essay: Teamwork and Perseverance

The Vendée Globe is a singlehanded sailing race, yet each solo skipper could not succeed without a skilled and dedicated team on land. This team has prepared the boat, and while the skipper is at sea, are on call 24/7 to advise the skipper by satellite phone on technical repairs or problem-solving. The entire endeavour is very much a group effort with the skipper being the point person at sea.

We have a team in the United Kingdom who are expert in the latest Open 60 technologies (electronics, sails, rigging, carbon boat-building, etc.), and a team in the United States who have installed equipment specified by the UK team. When the boat was in the USA, the UK team would come over and help the USA team. In this way, everyone got to know each other, and so although separated by an ocean, they are all on the same page regarding our boat, project, and effort.

Additionally, we have our sitesALIVE team, who are essential to our project’s mission of education. These include web experts, curriculum designers, program managers, and business experts to manage the relationships with our partners. Weekly, we have a Skype call that now includes both boat and sitesALIVE people to ensure that all communications that might affect the program are known by all.

I, as solo skipper offshore, am just the tip of the iceberg of our project. The real value is out there in the classrooms around the world – is it working for the teachers and for their students?

The topic of perseverance is natural since the voyage and the program are so long while they are operational. Yet our planning and development, both for boat and program, has been going on for even longer, for several years. All involved will require tremendous perseverance to get to the finish line. And so to see this through one can glean a lesson for many other aspects and challenges of life: you just have to keep at it, until it’s done.

Yesterday I went from 3 reefs to 2 reefs to 1 reef to the full mainsail. On the pedestal winch, that meant about 500 revolutions in a medium gear, or 1000 revolutions in a lower gear. I thought my arms, hands, and fingers would fall off! I was utterly exhausted at the end, but it had to be done for the weather conditions. Persevering paid off and we went quickly through the night with the correct sail for the weather conditions.

Essay: Teamwork, Perseverance & Asthma

When Rich Wilson was growing up, there were many mis-understandings about asthma. Many people still believed that asthma – with its cough, wheezing, shortness of breath, and tightness in the chest – was a psychological disease. Children with asthma were advised to sit out from sports and other strenuous physical activities, because exercise could provoke an attack of asthma. There were few, if any, famous role models with asthma whom a young person with asthma could admire and try to be like. Medicines to treat asthma were also quite primitive. They didn’t work terribly well and they often had unpleasant side effects, like nausea and jitteriness.

There have been major advances in our understanding and treatment of asthma since those times. We know now that for most children, asthma represents an allergic reaction of the breathing (bronchial) tubes. Muscles surrounding the tubes squeeze them into narrow passageways, and inflammation with swelling and mucus further plug them up. As you might imagine, exercise is good for the lungs as well as for the rest of the body. Children with asthma receiving proper treatment are encouraged now to play sports and be fully active without limitation. These days one can easily point to athletic superstars who have excelled despite their asthma, like Jackie Joyner-Kersee in track and field, Amy Van Dyken in swimming, Jerome Bettis in professional football, and, of course, Rich Wilson in sailboat racing. Also, our asthma medicines are stronger, safer, and simpler to use. For many people, that means simply taking one tablet once daily and perhaps one inhalation of medicine once or twice a day.

Although symptoms of asthma come and go, the tendency to develop narrow airways is present all the time for people with asthma. Asthma is a chronic condition. For many people with asthma, that means taking medicines every day to prevent asthma attacks and being on the alert to avoid things (called “triggers”) that might bring on asthma symptoms. Like sailing solo around the world, taking care of your asthma on a daily basis takes perseverance – not letting down your guard, even when things are going well. It also requires teamwork: patient, doctor, family, and friends, all working together to ensure healthy outcomes. Rich Wilson knows this: he takes his asthma medications every day; he checks his breathing frequently with a measuring tool called a peak flow meter, and he consults periodically with his medical team to ensure that he is getting the best treatments available. Smooth sailing takes perseverance and teamwork.

Essay: Fisheries Depletion

Living in New England, with the major fishing ports of Gloucester and New Bedford, one is exposed to the state of the fisheries. Over the course of the last half century, the major stocks have depleted significantly. For the Grand Banks off Canada, the cod stock, one of the most important in fishing history, is so severely depleted that there is a complete ban on cod fishing there.

Globally, similar situations exist. A challenge is simply the huge population explosion in the world. People need protein, and fish are a good source, if the resource exists. Yet, fishing technology continues to improve. I remember in 2002, sailing from Australia to Hong Kong between two of our clipper route voyages, we were about 1500 miles northwest of Papua New Guinea, when suddenly there was the distinct thwap-thwap-thwap of helicopter blades. 1500 miles from land?! There was a tuna fishing vessel with a helicopter flying out to find where the tuna were! Beyond not seeming fair to the tuna, clearly it was effective or they would not have been using such expensive technology.

I recall in the 1960s and 1970s, that population was a topic much written about, studied, and discussed. Part of the discussion was what will an expanding population do to resources, and, in fact, will constrained resources constrain the population? I notice that the topic of expanding populations has essentially disappeared from public conversation. It’s not just the fisheries that would be part of that discussion, but water resources, other food resources, and job availabilities. But if the discussion does not exist, no solutions will be sought or found.

Here, I have no scientific data on the fish below the boat. I do think that we had fewer flying fish coming on deck going through the tropics. We have perhaps had more tiny shrimp come on board than I recall from other voyages here to the south. Clearly, those two observations do not deserve to be part of the scientific discussion. Yet as with other topics, we must go to the experts, such as Dr. Ambrose Jearld, and the research performed globally for fisheries, for valid assessments.

Essay: Fisheries Depletion

As Rich sails across the world’s oceans he will not see the thousands of fish species living in the waters far beneath his boat or the smaller prey species and plankton that they eat. Fish is a growing source of food for people around the world, but as more people eat fish and the technology to locate and catch them improves, many species have been depleted (or are being depleted) by overfishing, climate change, and other factors. Satellites and advanced sonars or fish finders are making it easier to locate schools of fish, and new nets equipped with sensors are catching more of the available fish. Bycatch, or catching fish you aren’t trying to catch, is a problem because it doesn’t allow those species to reach reproductive age to replenish their population.

Warming ocean waters are causing many fish populations, which prefer certain temperatures to grow and survive, to move to more preferable habitats which could be farther offshore and away from current locations. The same is happening to the prey fish eat, and as the source of food moves so do the fish that eat them.

Another increasing problem in the world has been illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, which makes it very difficult to manage fisheries. It is a global problem that threatens ocean ecosystems and sustainable fisheries. Many governments, international organizations and private industry groups are working together to combat IUU fishing.

We want to be able to keep eating fish, but we won’t have enough for the future unless we allow depleted fish populations to rebuild and grow, and unless we keep other populations at healthy levels.

The good news is that fish are a renewable resource, and they can naturally replenish their populations if the right management measures are put in place.

As scientists we try to understand basic biological questions like how does each species of fish grow and reproduce, but we also need to know how the environment or ecosystem in which the fish live affects its behavior and life cycle. This way of looking at the whole picture (and not just the fish) is called ecosystem-based management, and it is being put into practice in many parts of the world. A number of depleted fish populations are recovering, but we have a lot more work to do.

As students, there are many ways you can become involved in helping to sustain fisheries around the world and especially in your local area. You can help track ocean currents through surface drifter programs (check out oceanographer Jim Manning’s drifter tracks), learning more about fish species that live in your area and catching only those fish that are not in danger of depletion.

Essay: Forces of Nature

At sea on a clear starry night, one likely feels exceptionally small when confronted by the enormity of the universe laid out in front of one’s eyes. It is impossible to describe the relative sizes, except to say that we are tiny.

Similarly, in a storm at sea, one will feel the immediate effects, on the boat, on the sailor, the force of the wind, the violence of massive waves, yet still, one only can experience that which is immediate and nearby, within one’s own horizon.

So when you look at the chart, and see that we have been sailing for 10 days since New Zealand, and that we have another 10 days to go to get to Cape Horn, how do you consider, and understand, that enormity of this Pacific Ocean? Or can you? In the storm that we had, how do you connect to the fact that that storm was hundreds of miles across? And that every little local area, as the area that affected us, will have similar forces of wind and waves?

I cannot comprehend that enormity. Yet I know that I can, and must, respect it. And perhaps this is the best that we can do in other areas of nature. We must respect it, both to defend our tiny physical selves from its enormity, but also to admire it and be amazed by it. We might consider the notion that these powers and forces were here long before we were, and in some sense, we are the intruders, or at the very least, the newest neighbors, for that which has existed for millennia.

The power of an earthquake, or the mass of water flowing down one of the great rivers of the world, the gigantic glaciers, veritable rivers of ice, the incomprehensibly massive oceans of the world – aren’t we lucky to be here to observe and live alongside such amazing and massive forces!

Essay: Forces of Nature

As a young sailor and before I became an Officer and later a Master Mariner, I remember an elderly gentleman telling me, ‘The sea is safe until you forget it is dangerous’. This is absolutely true when considering the forces of nature. Theses ‘forces’ can include wind, waves, swells, currents, volcanoes, hurricanes and typhoons.

In my 50+ years at sea, nature twice dictated that her forces would have me very concerned as to whether I would get home. The first was in an area South of New Zealand, where ‘Great American IV’ will transit. In these latitudes a swell train goes virtually around the world coming basically from a WSWly direction. This voyage an extremely strong storm sent winds from the NW and thus with the standard swell and the storm swell from two different directions, there was a very confused sea state. Being in a quite small research vessel, it was impossible to sleep for almost two days as we struggled our way North to make the shelter of an island at the bottom of New Zealand. It is times such as this, that diligent ship handling becomes very necessary, otherwise serious ship damage can be incurred, with possibly, the loss of the vessel herself.

The second incident was in the South China Sea when caught in a Typhoon with very little room to manoeuvre. Winds in excess of 75 knots, and a swell height of at least 10 metres dictated that we needed to heave to, with the weather on our Port bow and speed rung on for around 10 knots. While the vessel pitched and rolled violently at times, we were able to hold our course, however our ‘speed over the ground’ on GPS showed that in fact we were going some 3 knots astern. The situation lasted some 12 hours until the weather abated somewhat, at which stage we were able to come back to our correct course. What was the most alarming bit, came next morning when the Chief Engineer informed me he had needed to nurse the main engine all night as there was a problem with one of the cylinders. Given that the engine was to stop, we would have been in dire straits.

Underwater volcanoes are not rare in the western section of the Pacific Ocean. Extreme forces of nature can cause an underwater eruption which sends great clouds of steam to the sea surface, and given that this eruption continues over a long period of time, a small island can emerge. A classic example is the ‘Big Island’ of Hawaii. This started in the same way and over many thousands of years becoming as it is today, still forming further land mass. One product of these underwater volcanoes is pumice. Once while on watch crossing the Pacific, I glanced up from something I was doing and briefly thought we were about to run aground on a sand bank. Virtually totally impossible, the vessel having a very accurate position, but still extremely concerning. Eventuated that the ‘sand’ was in fact a large mass of floating, light coloured pumice, which had originated from a subterranean disturbance, more than likely a volcano.

Thus there comes from these few words, another saying: ‘Love the sea but respect it fully’.

Essay: Decision Making

Decision-making in my immediate context of a Southern Ocean gale is about risk and return. My goal is to get safely to Cape Horn. We have another 36-48 hours of this storm to go. That is a long time for the boat and skipper to be at risk. And we have an immediately sad example of that risk in the dismasting today of Enda O’Coineen’s boat on the other side of this storm.

So the first goal is to get through this storm. And the second goal is to get through the storm that is following behind it. So do we try to go faster, with more risk, in this storm, to be able to get out of the way of the second storm? Or should we be safer and more conservative in this storm, and then deal with the second storm when it arrives? After all, the forecast of that storm may change for the better, or for the worse, but it is far from certain now.

We have chosen to be safer now to give ourselves the best chance to get through this gale. Toward this, we have much less sail area up than is called for by the performance specifications of the boat. They want us to have 2 reefs in the mainsail, plus the staysail. We have 3 reefs in the mainsail plus the storm jib.

Another factor is that we must make sure that the staysail, our workhorse sail, is in good shape when we get to the Atlantic. So should we add any risk to that sail for the benefit of a few extra knots of speed in the storm? If we go a little faster, will that save us from the second storm? It gets complicated quickly!

Plus, for me, one has to sail according to one’s nature, and for me that is being conservative. If I have the storm jib, I can get some sleep in and be better rested than if I have the staysail and are going faster, but bouncing and ricocheting off the waves, and unable to sleep.

Every decision, at sea or in life, has different inputs to the risk and return equation. They must be weighed carefully with their consequences to attain a final decision.

Essay: Decision Making

When was the last time you had to think hard about making a decision? Often our everyday decisions are easy, and the consequences aren’t likely to be life or death. At other times, decisions can be very difficult and the decision that you make can have life altering effects. Making difficult decisions can be broken down into a specific step-wise process that can help lead to positive outcomes. What is your goal and will your decision help get you to your goal?

When I work in the emergency department, my team is constantly making decisions that affect our patients. We must decide which patient to see first (the sickest usually get priority) and then decide what we need to do to make someone better. Some decisions are hard to make and sometimes we need to do things that may be uncomfortable for our patient, but in the end, we know that our patient will get better, which is our goal. Above all else, we need to make sure that we “do no harm.” We strive to make good decisions so we don’t make our patients worse.

Rich is also constantly making decisions that will allow him to finish the race in the fastest time possible for him. Some of Rich’s top priorities are for his boat and for himself. While he makes hundreds of decisions every day, the first questions he must always answer is what effect will his decision have on his boat or on himself. Will more sail or less sail protect the boat? Should he take a nap or stay awake? Should he go faster and finish sooner or slow down and be safer?

Rich recently encountered a violent weather system and if he had maintained his boat speed, he would have run directly into the worst part of the storm, potentially damaging his boat and maybe himself! Instead, he made the decision to slow down, letting the storm pass in front of him and avoiding very dangerous sailing conditions. In mid-December, another Vendée Globe skipper, Jean-Pierre Dick, took a huge detour passing north of Tasmania and through the Bass Strait to avoid a similar storm. No other skipper had sailed through the Bass Strait during the Vendée Globe- it is far from the shortest route around the world, but these decisions worked to preserve the skipper and the boat.

Remember, without an intact boat and an intact skipper, there can be no successful race- and that is the goal to keep in mind when making decisions in the Vendée Globe!

Essay: Wildlife

Often I am asked – don’t you feel confined in that little boat? And my answer always is – not at all! Because where else can you live every day, all day, with a 360 degree view of the horizon and a hemispheric dome of sky overhead?

Immersed in open nature this way, one finds oneself in the world of other creatures inhabiting the same space. We’ve had tiny shrimp, squid, and flying fish all come aboard, as well as what looked to me like a baby Portuguese Man-of-War. Groups of dolphins have escorted us.

And in the sky, we’ve had stormy petrels, terns, and the enormous Albatross, a bird that almost never flaps its wings, but just soars and glides on the wind and its updrafts and downdrafts over waves. Plus myriad other birds that I can’t identify, my knowledge being inadequate.

For all of those creatures, this is their natural environment. For me, it’s not my natural environment, I am the intruder – or the guest – in their domain. Of course we must respect that domain by not polluting, but we must also appreciate it for its diversity and astonishing accomplishments. Look at all the things that those creatures can do that I cannot do! They are amazing! How did the albatross learn to fly like that?! How did the flying fish ever figure out to leap out of the water and glide on their fins as wings for 100 meters to escape predators?!

No, this is not confinement. This is good fortune to be here and to see all of it.

Essay: Marine Life

Sometimes it feels lonely sailing around the world alone on a small boat on a big sea. Except Rich Wilson hasn’t really been alone.

He’s joined from time to time by other living creatures—creatures with lives as wonderful, and journeys as compelling, as his own.

Some of them flop right up on deck. Flying fish use wing-like pectoral fins to get themselves airborne, gliding for up to 655 feet before splashing back down again (or getting dumped back overboard with Rich’s help.) The fish do this to escape predators like marlin, swordfish, and tuna–who surely aren’t expecting their prey to leave the ocean, even for a short period!

Many billions of other animals float, swim, crawl and sit beneath and around and sometimes on the Great American IV. Rich has glimpsed a few of the stranger ones: squid, who can taste with their skin. Shrimp, who like lobsters, wear their skeletons on the outside instead of inside like us.

But without Rich even seeing it, he knows that creatures from whales to corals (who look like rocks but are really colonies of tiny animals) are doing extraordinary things beneath the waves he rides: Humpback whales are singing complex and beautiful songs, which they change from year to year. Crabs with hairy chests huddle near undersea volcanic vents in the icy Southern Ocean for warmth, and farm bacteria on their chest hairs which they scrape off with special mouthparts to eat. Brainless jellyfish are choosing to split into pieces to make copies of themselves.

The ocean is our planet’s largest wilderness. Yet so many of its creatures seem to us like outer space aliens, they are so different from us.

But one magnificent creature keeps Rich company from time to time, and these two have a lot in common. Both are riding the wind. Both are on epic, long-distance journeys. And both will be spending months on end without seeing others of their own kind.

The albatross has the longest wingspan of any bird—more than 11 feet for the largest kind, the wandering albatross (there are 22 species). With its snowy white body and grey wings, the bird looks rather like a sea gull crossed with a limousine. It’s a spectacular sight many mariners like Rich have enjoyed through the ages. An albatross will often follow a boat, hoping for a handout from the crew, or at least some tasty fish guts tossed overboard. So it’s no wonder that albatrosses occupy a special place in maritime lore.

Some sailors believed that the albatross carried the soul of dead sailors—and seeing one was good luck. The soul of the dead sailor, some insisted, would protect them from harm. Others though the bird was a bad omen, foretelling the death of a seaman.

The truth about these magnificent sea birds is even more amazing. Without even flapping once, an albatross can glide for hours and cover several hundred miles! No other creature can do this. The bird’s secret? It’s called dynamic soaring. They spend half their time gaining height by angling their wings while flying into the wind. They then turn back toward the sea, swooping along at speeds up to 67 miles per hour, till they catch another updraft skyward. And do it again and again, expending remarkably little energy. By studying exactly how they do it, engineers are trying to design more efficient airplanes.

Rich and his albatross friend also face a common enemy at sea. Two of the other boats in the Vendee Globe have already been knocked out of the race by “UFOs”: Unidentified Floating Objects. Smaller UFOs threaten albatrosses as well, though in a different way. Albatrosses eat mainly fish and squid, but there’s so much trash in the ocean today that many of them are eating plastic by mistake! They even mistakenly feed plastic to their babies when they finally alight and nest each year on land. We humans are such slobs with our garbage that by the year 2050, scientists say there will be more of our plastic in the ocean than fish!

Many seabirds, as well as whales, dolphins and sea turtles, choke or die of starvation with stomachs full of trash. Numbers of many of these creatures are crashing. And that makes a special albatross named Wisdom particularly important. Wisdom, a Laysan albatross (who wanders the North Pacific), is the oldest seabird in the world—and as this article is being written, she’s incubating an egg!

So Rich—the oldest sailor in the Vendee Globe race–and Wisdom, the world’s oldest seabird– have something else in common: they both are showing the world that no matter how old you are, you can still do something wonderful to enrich our precious blue planet.

Essay: Midpoint

A midpoint invites you to look both forward and backward in a project.

Looking backward, are we attaining our goals that we stated at the start? For this project, it was to sail well, to tell the story of the sea to those on land, to deliver all of our promised sitesALIVE content, and to finish the Vendee Globe.

Did we achieve these? Slowly we are sailing better to the capacity of the boat and the skipper is learning that his capacity may be bigger than he thought. We have created some problems of our own to solve (batten car) and we have solved some problems not of our own making (hydrogenerator pump). We have told a detailed story, but perhaps it has been too much on the sailing side and not enough on the life and humanity side of the Vendee Globe. We have delivered our promised content, but also with the aforementioned imbalance in focus perhaps. We have not yet finished the Vendee Globe.

So for the second half, we shall try to attain a higher percentage of the boat’s capacity, while acknowledging that our natural conservatism has served us well so far. We shall work on telling more of the human side of the story rather than just the boat numbers. We also know that chance or luck has a big role to play (Vincent, Kito, Thomas hitting objects in the water) and we hope that King Neptune will continue to smile on us, and the rest of the fleet, and let us all pass.

Almost nothing makes me happier out here than that you teachers and students have chosen to participate with us in sitesALIVE! When I get tired, or discouraged, or afraid out here, I have come to say to myself – you’re out here for the students, teach them what you can, tell them the stories, help them to learn – and I am reinvigorated. You truly are helping to bring me home. Thank you.

Essay: Midpoint

When preparing Rich for his Vendée Globe voyage, we worked on three aspects of his training. One was getting him physically prepared, another was mental toughness and the third was training him emotionally so that he would be able to better deal with extenuating physical or mentally exhaustive days and nights on the boat. Each workout had a beginning, middle and a final stretch very much like what he is doing while racing, although on a much smaller scale. We would begin each workout with a warmup period. He would do a five minute dynamic warmup increasing blood flow the muscles in his body that we were going to be working. We would then concentrate on core strengthening.

At the Midpoint of the workout we would be focusing on training his muscles to have as much strength, endurance and agility as possible. The Midpoint of each session was the toughest section of the workout because it had the most intensity. We were exhausting him physically which also simultaneously exhausted him mentally and emotionally. During this section of each workout I would remind Rich to stay focused, to take it one exercise at at time, one rep at a time. I knew if he could get through this section of the workout the rest of the workout would be smooth sailing!

The middle section of any competition is always humbling. It is the time when your mind wants to drift, your body wants to quit and you may question why you are doing it. Rich is probably having some of these thoughts right about now but I am confident that because of his preparation, both physically and mentally, he will not question whether or not he can finish but will instead look ahead with excitement to completing his race. He may have a few moments of doubt for that is part of being human but I know that positive thoughts will mainly be filling his mind. I believe that once he passes through that Midpoint of the race he will have a sudden surge of confidence that he is well on his way to a very successful voyage.

Essay: Climate Change

When we sailed east past Marion Island in the Indian Ocean a few days ago, we were 220 miles further north than when we sailed past here in Vendée Globe 2008. Then, as now, there were course restrictions for safety from icebergs breaking off Antarctica that we had to stay north of. Although we never sailed precisely at those limits, it’s interesting to note that the Antarctic Exclusion Zone (Vendée Globe 2016’s iceberg protection) is much further north than the series of ice gates in Vendée Globe 2008.

Of course my observation of this, and race management’s placing of the ice constraints, do not constitute scientific data. But they compel me to ask our Climate expert Dr. Jan Witting whether there are more icebergs breaking off Antarctica due to a changing climate, or not? Or perhaps there is another reason that the hazard has moved north?

Research in Greenland tells that the glaciers there are melting and receding. This is known by on-site researchers, who go back year after year to establish trends in one direction or another, and by satellite photographs. Similarly for the Arctic Ocean ice, satellites show that the coverage of ice is getting smaller. The same goes for glaciers in the Himalayas.

Do any of these data persuade on their own that the climate is changing? No, but the consensus of evidence globally is substantive, and one can conclude that, yes, the climate is changing. It all rests on the data, and we must look to those experts in the field for that data, and for their insights. We can wish or hope that the climate were not changing, but we cannot deny facts.

Essay: Climate Change

As the Great American IV speeds along the South Atlantic, the ocean will look much the same to Rich as it did during his race in 2008. But if you look closely, there have been some pretty big changes in our global ocean and in the climate of our planet. Let’s start with the biggest factor in human-caused climate change: Carbon dioxide in our atmosphere has steadily increased. In the eight years since 2008, its levels have climbed from 385 parts per million (ppm) to 407 ppm. Is this 22 ppm change a lot or a little? Measurements from air bubbles trapped in ice long time ago in the Antarctica show that this increase is much greater than what happened in the 2000 years before our industrial age. It is a lot, and it is happening quickly!

What does this mean for the ocean? Just like our atmosphere, the ocean has warmed also, but not the same everywhere. In places like the Arctic Ocean, the increase has been a lot. But elsewhere, like in the Southern Ocean that Rich is skirting right now, the ocean may actually have cooled a little. Why? The answer is the wind. What makes the wind blow is the difference in air temperature and pressure between two points. Cold air is denser and results in higher atmospheric pressure, and this high-pressure air wants to flow toward warmer, lower pressure, areas. As the planet’s atmosphere warms, these differences in hot and cold are getting bigger. An example is the difference between the Antarctic cold air and the surrounding sub-tropical warm air, and the result is that the winds in the ocean around Antarctica are getting stronger. These stronger winds cool the ocean through evaporation, just like, if you are a little sweaty, you’ll feel the wind start chilling you!

That, though, is climate, and what Rich has to worry about is weather—the storms and calms that our changing climate spawns. From a climate perspective, you’d predict that the storms on average have become a little stronger, but that doesn’t mean that all storms are more intense. Either way, let’s wish Rich and all the other skippers luck to avoid the worst ones!

Essay: Antarctica

In Captain James Cook’s day, it was thought that there must be a Great Southern Continent that would balance the weight of Europe and the Americas on the globe. In 1774, he sailed deep into the south, incredibly to 71 degrees south, trying to find it, but without success. The first known landing on Antarctica was purportedly by the American sealer Cecilia, at Hughes Bay in 1821. The continent has lured the great explorers: Scott, Amundsen, Shackleton and others. They wished to get to the South Pole. Now this land continent houses researchers of many varieties and nationalities. In fact the Antarctic Conservation Treaty, which manages the continent, must be deemed a great diplomatic success, as there is to be no militarization of, nor mining on, the continent, it must remain ‘pristine’ for several decades to come. Important research on climate change has been done in Antarctica by measuring ice thicknesses on land, and whether more or fewer icebergs are breaking off from the continent into the sea. We see this in the Vendée Globe, where, to keep the competitors safe from accidentally running into an iceberg, there has been established an Antarctic Exclusion Zone, where we cannot go. Satellites are taking pictures of icebergs, but they can only see ones that are bigger than 80 meters long. As icebergs move north into warmer water, they break up into sizes unseen by the satellites. Even in our race so far, because of these observations and interpretations by experts, our AEZ has been expanded 5 times. From various expeditions to Antarctica, one sees fabulous photos and videos that ‘take you there’. But I would like to see it and feel it and hear it for myself! Just as I make plans on the boat for the coming days, it’s time to make a plan to see Antarctica in the coming years. When one has a curiosity, it must be pursued.

Essay: Polar Art

I write this just as Rich has begun rounding the southern tip of Africa at 40 degrees and 27 minutes south and has begun some of the most arduous sailing, highest wind speeds and biggest waves he expects to encounter. He has entered the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which rings the Antarctic continent and essentially passes through all the major oceans. For racing sailors like Rich, sailing into the strongest current in the world has obvious benefits as it will carry him very quickly. For centuries, however, this current and its extreme conditions proved a formidable barrier for ships sailing south.

During the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries – the age of exploration – theories about a vast southern continent were based in notions that land on the earth’s surface somehow had to be balanced, and since there was so much land in the northern hemisphere, there had to be an equivalent amount of land to the south. Some of this imagined land even appeared ringing the bottom of world maps, labeled Terra Australis Nondum Cognita, Unkown South Land. They had never seen it, but they felt sure it must be there.

Although their theories were wrong, the land at the bottom of the world does, in fact, exist. Captain James Cook encountered a vast field of icebergs during his second voyage in the 1770s and his official on-board artist drew sketches and ultimately an engraving of it to illustrate the voyage account. By 1840, several expeditions claimed to have sighted the Antarctic mainland. A fabulous print by the French expeditionary artist Louis Le Breton shows men climbing excitedly onto rocks from small boats with penguins standing by watching – the whole scene surrounded by towering icebergs. The hazards of floating ice ringing Antarctica inspired traveling artists for many years following, no doubt in part because their size evoked a sublime sense of nature and its dangers, and were more overtly dramatic than the relentlessly barren snowfields inland. Antarctica is a magnet for artists to this day, many of who revel in disproving our notions of it being a barren and colorless environment. Since the 1950s, the Antarctic Artists & Writers Program of the National Science Foundation has sponsored the work of more than 100 artists who desired to visit Antarctica in the course of their work.

Essay: Invisible Places

At sea, we see great swaths of ocean, and thereby of the planet. Sometimes on a long ocean voyage, we may be close to land, but more often we are hundreds of miles off any land. In either circumstance, I like to think about the people, the places, the cultures – just over that horizon!

In this voyage, we were near Cape Finisterre, and I could see the lights of Spanish towns. On our 2003 voyage Hong Kong to New York, we passed between Java and Sumatra in Indonesia, and could smell the spices of Sumatra. On our San Francisco – Boston voyage in 1993, we saw the lights of Recife, Brazil as we sailed past, and later were covered by dust blown two thousand miles from the Sahara Desert. These were direct connections to the lands we passed.

Yet if there is no such direct connection, you must use your imagination. Who are they just over there? What language do they speak? What religions to they follow? What is their culture like, and their art, literature and music? What is the geography and topography, the politics and the government?

It’s a simple and friendly curiosity about our neighbours on the planet. Likely, they are more similar to how we are, than they are different. Likely they too will want a peaceful existence, good health for their families, adequate food and shelter, and a brighter future for their children than they themselves might have had.

Just as a huge night sky full of stars lures one to imagine one’s place in the universe, this imagining among mariners about who and what lies just over the horizon, helps us ponder our role and place on earth.

Essay: Invisible Places

The first time that I went to sea on a boat (I was 5 years old), I felt several very strong feelings: entering another world with different colors, a different smell and different sensations; the impression of travelling on a living being, which moved and smelt very salty. I also felt a certain humility, the impression of a great vulnerability but also the strong desire to discover, to experience and tame this world full of mysteries.

The first time that I crossed the Atlantic Ocean, I discovered the immensity of this liquid dessert and I realized that our planet was really very big. We were heading westward, towards America, the days and weeks passed and we still hadn’t seen land in front of us yet. Life seemed absent: no sea birds or fish and few whales. A solitary and wild world, with no other guide than the stars and so far from man and civilization.

At night we progress without seeing the landscape pass-by, the celestial sphere is our only vision and we feel alone in the universe.

In the day, the sea is there with the waves, the clouds, the sun and sometimes a sea animal or a bird of passage; we can get very close to land without seeing it and that is very frustrating. I remember having come close to the island of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean; the land was roughly twenty miles away and we could smell the slightly spicy odor of its vegetation, see the coastal clouds and simply sense the presence of this great island, but there was nothing on the horizon, it was as though the Earth was imaginary.

The competitors in the Vendée Globe Challenge will cover over 24,000 miles, or right round our planet without ever seeing land unless it is a few faraway summits of some isolated island. For three months they will only see millions of cubic metres of salty water that make up the sea and the oceans. In these great desserts of solitude that they will cross, civilization will seem very far away to them and everyone, at a given moment, will wonder if mankind still exists. Is it real? It is in these great liquid desserts that man feels insignificant and vulnerable, and it is there, more than anywhere else, that he must be aware of the need to preserve and protect what is, after all, a fragile sphere of life.

Essay: Marine Pollution

Today is a beautiful day at sea. We are 300 miles east of Recife, Brazil, the blue sky has fluffy clouds, and the sea, cresting with an occasional whitecap, is a deep blue glittering with sunlight. Does the ocean look polluted? No, it looks beautiful.

But just because it doesn’t look polluted, doesn’t mean it isn’t. I only see a narrow swath, on either side of the boat, and only in daytime, and only if I’m on deck. To answer the question properly, we need to Ask an Expert. If we were buying a house, we’d consult a real estate expert, if we were sick, we’d consult a medical doctor. We need trained, data driven, environmental scientists to guide us by their research, not just opinions.

And what do the experts say? They say that the oceans are polluted, and are getting more polluted. Is there a Great Atlantic Garbage Patch so densely polluted that you could walk across it? No, not in the way that the media portrays it. But there is a large area of high concentration of microplastics that are there only because we humans let them get into the ocean, and then they found their way there through ocean currents.

The plastics are a problem because they get into the food chain of fisheries, and we need fish as a protein source. Oil pollution along coasts is problematic due to contamination of wetlands. Chemical pollutions of rivers and stream is problematic for drinking water and fishing.

To create solutions for these problems, first we need to know the extent and characteristics of the problem. And for that we need data-driven research, the skilled scientists to interpret that data, and for the non-expert public to listen to the experts.

Essay: Plastic in Our Oceans

Do you ever wonder what happens to a plastic drinking straw after you are finished using it and throw it away? Where is “away”? Where does it end up?

The answer depends on where in the world you live. In some places, the straw is probably buried in a landfill, or burned to produce energy in a power plant. In other parts of the world where there may not be enough garbage cans, or garbage trucks, or places to safely contain this trash, the plastic straw might end up in a river, or on a beach, or in the ocean.

An estimated 8 million metric tons of plastic waste enter the oceans each year. That’s enough plastic trash to line the entire coastline of the world with a stack of 5 plastic grocery bags chock-full with plastic garbage. What happens to this plastic?

Most of the plastic packaging that we use breaks down into floating fragments, smaller than your pinky fingernail, that collect in vast regions of the oceans often referred to as “garbage patches”. These are not giant landfills, or plastic islands made of trash, but instead consist of millions of tiny pieces carried by ocean surface currents to dead-end collection zones in the oceans.

Marine animals as small as plankton and as large as whales can eat these small plastic bits, and so can the fish and shellfish that we enjoy as seafood. We’re not sure what effect the plastic has on the animals, or if there is any harm to humans who eat them, but surely you wouldn’t choose to eat plastic for dinner!

The best way to stop this plastic pollution is simply to use less plastic. Skip the straw. Choose reusable containers and bags instead of those designed to be thrown away after one use. Recycle when you can. And teach your friends and family about this pollution problem that we can all help solve by making small changes in our daily lives.

Essay: Equator Crossing

For a mariner, Crossing the Line is a special event, no matter how many times he or she may have done it before. North turns to South (or the reverse) on the GPS. The Line is not marked by buoys, only by signs (+ or -) in the spherical trigonometry of the planet.

New stars and constellations appear that cannot be seen from the other side of “The Line”. Polaris, our celestial anchor in the Northern Hemisphere, will disappear below the horizon in our wake when we cross heading south.

In a maritime tradition universally followed, those who have Crossed the Line must initiate those who have not. The ceremony is to degrade and interrogate as to whether they are worthy of entering King Neptune’s new domain, which must be respected. The Ancient Mariner offended King Neptune by shooting the Albatross, and brought disaster to his ship.

I have crossed the line eleven times under sail and once aboard cargo ship (New Zealand Pacific, after our rescue off Cape Horn in 1990). Even aboard The Big Red Lady (NZP’s affectionate nickname), merchant mariners who had not crossed were ceremoniously doused in bilge water and diesel sludge, demeaned, questioned, demeaned some more, and then permitted to cross. I was happy to see that these highly professional mariners still adhered to this tradition of the sea.

When we cross in a few days, I will wonder, as I did in 2008, what adventures, inspirations, calamities, marvels, and rigors will happen to us before we re-cross going North. We will have gales, we may see the Aurora Australis, we will suffer the cold and the fear, before rounding Cape Horn and heading north again. The South, how will we fare in the South? We will do our best; yet King Neptune will decide.

Essay: Equator Crossing

People often speak of drawing “a line in the sand,” meaning a boundary that cannot be crossed without serious consequences. Next week Skipper Rich Wilson will cross a line in the water. Although no one can see that line threading through the ocean waves, still the Equator constitutes a real borderline between the northern and southern hemispheres. At the Equator, the Sun and planets pass more nearly overhead, the temperatures at sea level change little with the seasons, and the girth of the Earth is widest. Perhaps most important for the person sailing from north to south, the Equator marks a ship’s passage into the mythic realm of King Neptune.

The slow winds—or no winds—in the so-called doldrums near the Equator left European sailors of centuries past plenty of time for mischief. The old experienced hands would put the new recruits through a rite of passage that could include smearing their heads with foul slops, “shaving” their faces with jagged bits of iron that pierced the skin, pouring salt water down their throats, flogging them, and pitching them blindfolded into makeshift pools (sails filled with seawater). One senior sailor would dress up as King Neptune and preside over the shenanigans. When the initiation was over, the crew headed into whatever dangers awaited them in the southern ocean.

On ships that observed such line-crossing ceremonies, no first-timer could demand exemption. Charles Darwin experienced the indignity aboard HMS Beagle in 1832, en route to his encounter with the interesting wildlife of the Galapagos Islands.

Rich has plunged southward across the line several times before. Even if he were making his first crossing now, there would be no one else aboard Great American IV to induct him —except, perhaps, old King Neptune himself.

Essay: Marine Transportation

Shipping is an unseen, yet essential, industry. Around 90% of the world’s goods are sent to their destinations by ship. On land, if you live near a port, you might see a few ships from time to time. At chokepoints for the movement of ships, Panama and Suez Canals, Straits of Malacca and Gibraltar, you can see many ships, of many types, densely packed.

Last night, we passed Cape Finisterre (“end of the land”), at the northwest corner of Spain. Ships coming from South America, Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, and from Asia via the Panama Canal, that are going to ports in northern Europe, all come around this corner, in one direction or the other. This congestion presents a collision risk, and combined with the ferocity of winter storms in the Bay of Biscay, it was deemed important to organize ship passage around this sharp corner. Thus, like painted lines on a highway, the chart shows Traffic Separation Zones, and ships must go in their lane. There are four lanes, each is 4 miles wide, and the entire zone is 22 miles wide.

Ships are identified (by position, direction speed, and type) on our computer chart by AIS (Automatic Identification System). Last night I saw a tanker, a wheat carrier, a cruise ship, multiple container ships, and a general cargo ship.

Aboard New Zealand Pacific in 1990, after they rescued us off Cape Horn following our double capsize, we spent 18 days going to Vlissingen, Holland, and thus came around this corner (and into a Biscay gale!). The ship was the largest refrigerated container ship in the world at the time. The ship was fascinating in its technical complexity and the crew was astounding in their skill, diligence and hard work to keep that complex ship functioning properly in its hostile environment. And all unseen by people on land!

The next time you fill your tank with petrol carried by tanker from abroad, or have a sandwich with bread made from Australian wheat brought by bulker from down under, or slip on a pair of running shoes brought by containership from the Far East, think of those hardy souls aboard the ship who brought those to you, and thank them for their skill and expertise!

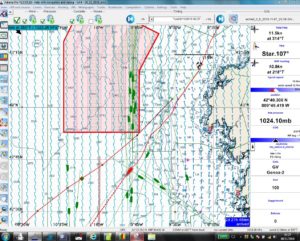

Cape Finistere Traffic Separation Zone. Great American IV is the red boat heading southwest. Green are ships entering the northbound lane as identified by AIS. Ships do not appear in the other lanes because the range of AIS is not long enough for us to see them. Green boat behind Great American IV, also heading Southwest, is Alan Roura, Swiss skipper for Vendée Globe.

Essay: Marine Transportation

Most people go about their daily lives never thinking about how the goods they use every day end up in their home. World trade is bigger today than ever before in history, and 98 percent of everything that comes to the United States and most other countries arrive by sea. Only passengers and some very small packages arrive by airplane. Giant tankers weighing as much as 330,000 tons carry crude oil for refineries. Smaller product tankers take gasoline jet fuel, and heating oil from refineries, to our nearby ports for distribution. Bulk carriers as large as 440,000 tons transport iron ore, coal, alumina, corn and wheat, and other “dry” commodities. Car carriers- big floating 13 deck parking garages- carry as many as 8000 automobiles. Containerships- today the worlds biggest ships – can carry as many as 20,000 containers, each the size of an 18 wheel truck. Millions of these containers packed full of manufactured goods arrive each year.

But shipping is a “hidden” industry unless you happen to live on the shoreline in a major seaport. Ships spend over 90 percent of their lives at sea over the horizon, only seen by other ships or curious dolphins. In the days before high seas radio was invented by Marconi, when a ship left port one of two things happened: she arrived safely at her destination, or she was never heard from again. Over the centuries thousands of ships and hundreds of thousands of sailors have disappeared. About 110 years ago, radio and the use of Morse code changed all that. The famous tragedy of the Titanic in 1912 was not the first use of radio for rescue, but it was the most famous “SOS” in history. The ocean liner Carpathia heard the SOS and arrived a few hours later to rescue about 700 survivors of the original 2000.

Merchant (non-military) ships generally have a crew of 20-25 trained mariners of many nationalities. These professional sailors live pretty isolated lives when they are on board, connected to the world through satellite communications only. Typically a sailor serves on board for about six months then rotates home. Most mariners are men, although women are now getting more involved in seagoing careers. There can be a lot of stress on families given the separation, so the increasing availability of satellite communications is a good thing. It is through satellite that Rich Wilson will be communicating with all of us during the Vendée Globe. But he will still be pretty alone and lonely in some very remote parts of the Earth, where the nearest rescue will be his fellow competitors.

Essay: Following Your Dreams

When I was a young boy, I read about the great solo circumnavigators: Joshua Slocum, Francis Chichester, Bernard Moitessier. Their adventures, courage, skill, and pursuit of their dreams mesmerized me. I wondered whether I could ever be smart enough, strong enough, or brave enough, to try something like that.

I also discovered a love for teaching, and for showing students the opportunities that exist for them in this world. Not until my middle age did my two passions combine, and we connected our first ocean adventure into classrooms to teach science, geography, and math in the real world. Voila! sitesALIVE!

Some may find their dream early, and some may find it late, but you only find it if you keep pursuing it, and keep preparing for when you do get there. As they say for the Vendee Globe, you can’t win if you don’t finish, so you must keep on working toward the things that you love.

My mother was the original adventurer in our family. She grew up in Tacoma, Washington, and after college, went to Fairbanks to host a radio show called Tundra Topics at KFAR, the first radio station in the Alaskan Territory. What must it have been like to be a single woman on the Alaskan Frontier in 1940?! She always modestly said: “I had great opportunities.” I admire my mother for saying “Yes” to those opportunities, as many would have said “No”. She knew the outcome was uncertain, but she took the risk instead of staying in her comfort zone.

This sitesALIVE program attains a dream of mine that we’ve worked toward for 25 years: a truly global school program connected to a truly global event. The boat is ready, I am ready, sitesALIVE! is ready. Now we embark on a great adventure with an uncertain outcome at sea. Yet it is surely worth the risk. Welcome Aboard!

Essay: Following Your Dreams

I have never wanted to do anything else but study space. I grew up in anthracite country in eastern Pennsylvania, where there were no professional scientists or nearby colleges where one could be exposed to enrichment programs in science. But living there worked for me because at night the skies were dark, and that is what I really needed most. While in elementary and middle school I checked out textbooks from the library and taught myself astronomy, physics, and optics. With the help of my grandfather, a very smart man who left school in eighth grade to work in the mines to support his family, I built telescopes to observe the night sky. And I spent hours and hours doing so, learning the positions of all the bright stars, and the locations of major galaxies and nebulae. I observed all the planets except for Pluto (which was a planet back in those days).

I attended the University of Pennsylvania to study astronomy and geology, and then Brown University where I received my master’s and Ph.D. in planetary geophysics. After completing my education, I went to the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and got involved in robotic missions to Mars and the Moon. Because I wanted to work with students I moved on to faculty positions at Johns Hopkins University and then MIT. I have had the extraordinary opportunity to work on many space missions with great colleagues and students at universities, NASA centers, and industry. I work hard, but I explore the solar system for a living and what could be better than that? Imagine what it would be like if your job could be your hobby? That’s the life I lead.

Essay: Preparation

Michel Desjoyeaux, the only two-time winner of the Vendée Globe, once said “the race is won before the start”. In other words, preparation is everything.

The three parts of our program which we must prepare are: the skipper, the boat, and our school program sitesALIVE! Fortunately, we have terrific teams for each who are smart, experienced, creative, dedicated, and hard-working. Although this is a solo race, I will not sail only for myself. I will sail for our teams, and for you students, as you are the most important reason that we are doing this.

For my physical preparation, I trained again with Marti Shea (see our Team of Experts). Marti is a former All-American distance runner and World Champion cyclist, and is an imaginative and demanding trainer. She said that, except for natural degradation of fitness due to age (she estimated 5% loss), I am in as good shape as I was 8 years ago when we sailed and finished Vendée Globe 2008-9.

Left to right: Rich Wilson, Joff Brown, Jonathan Green, Rob Sleep, Olly Young, Hugues Riousse

For the boat, Great American IV (formerly Mirabaud, with Swiss skipper Dominique Wavre, and built in New Zealand in 2006), our technical leader is Joff Brown (English), who has been captain for three successful Vendée Globe boats. His attention to detail is astonishing. It is the correct approach, since the Vendée Globe can succeed or fail on the tiniest of details within this highly complex machine that must thrive in a hostile environment.

For our sitesALIVE program, we have a multi-talented team led by Rick Simpson and Lauren Zike. They oversee our global partnerships and content distribution in 50 countries and 4 languages. Our curriculum is ready, the website is ready, and our Team of Experts is ready.

We have been three years in these preparations – and now it’s time to sail!